Today marks the 6th day of Black History month. This year’s theme is Black Resistance. While at first blush, the term resistance may conjure up memories of Malcom X or the Black Panthers, in reality, Black Americans resist in more subtle and nuanced ways every single day.

In the aftermath of the tragic death of Tyre Nichols, focus turns to the SCORPION Unit, tasked with targeting crime hot spots to reduce crime by utilizing man-made algorithms that target violent criminals knowing full well some criminals will not get caught, while completely innocent citizens will be incorrectly targeted.

Watching the Tyre Nichols traffic stop escalate into a five-on-one street brawl where Mr. Nichols never had a chance, made me realize that Black Americans in this country have had a history of resisting poorly developed, man-made algorithms that are more likely to harm us, rather than to help us.

Below, I describe how a similarly poorly designed, man-made algorithm almost changed the trajectory of my life and my career in an excerpt from my newly published book, The Way Up: Climbing the Corporate Mountain as a Professional of Color.

The book also shares my narrative about embracing defining moments in your life to discover self-worth and pride, as well as reclaiming your seat and reaching your full potential. For me, it was a journey that led me from the warehouse of a beauty supply store to becoming COO of a major health plan. Imagine what we all could achieve if society focused on algorithms designed to build people up, instead of tearing us down.

EXCERPT from The Way Up: Climbing the Corporate Mountain as a Professional of Color

For the rest of my life, society will not just expect me to walk on eggshells, to act mature, to forgive and be emotionally intelligent—but will also demand me to comply. My life depends on it. This lesson helped me navigate the most defining racial memory of my life, which was soon to happen.

As a senior in college, I was “stopped and frisked” at gunpoint by police on the streets of The Bronx more times than I could count. The first time I trembled in fear. By the time I graduated, it had become a routine dance. The uniformed officers would inevitably ask for identification, and I would reluctantly produce my driver’s license and Fordham ID card—always both.

Stop-and-frisk was a New York Police Department (NYPD) racially biased profiling policy that led to the temporary detention, questioning, and often search of New Yorkers just living their daily lives—whether they were suspects of a crime or not. My most severe altercation with the NYPD left me lying on a cold street in The Bronx one night at 11 p.m. My cheek was pressed between the concrete side-walk and the knee of a New York City police officer paid to serve and protect me from the very same people he suspected me of being. He was twice my size, and he used all of his body weight to pin me to the ground despite my lack of resistance. I remember the incident so clearly that the neighborhood sounds still whisper in my ears. The onlookers with their pointing fingers already condemning me. The corner bodega boys who scattered once the police sirens turned on. The cars that slowed down as they passed through the intersection of 183rd Street and Arthur Avenue, trying to get a glimpse at was happening under the glaring luminescence of streetlamps.

This corner was known to Fordham students as the “Bermuda Triangle” because there were three bars and a pizza shop at each point of the intersection. It was far enough away from campus to be cool, but close enough for drunken Fordham students to make their way home without being assaulted. Many Fordham students circled around the triangle as they traveled from one bar to another before ending at the pizza joint at 2 a.m.

As I lay on the ground considering my fate, it was in that unending moment that I realized I was truly Black in America. Guilty before proven innocent. At first, I was embarrassed; in fact, mortified. For the next few years, I told no one.

I was arrested because I matched a broad description of a Black male suspect with blue jeans and a white T-shirt. No height specifications or any other description, not even facial features to speak of. Just a generic young Black man sought in connection to a recent stabbing that had occurred nearby. This wrongful arrest led police to issue me a Class E felony charge of resisting arrest.

Resisting arrest! I was arrested by plainclothes policemen who offered no reason whatsoever as to why I was being stopped, or whom he and his fellow police officers were pursuing. Resisting becomes the first logical action when strangers step out of a car and put their hands on you. I remember realizing that I would live longer if I complied even though the police officers had yet to identify themselves. But that is exactly when I voluntarily went to the ground and put my hands in front of my head, signaling the white flag.

Despite this gesture of peace, two officers still tackled me hard even though I was already on the pavement. I know they barked orders, but I don’t recall what they said. They were loud, burly, and abrupt. Menacing in an almost demonic way. I just remember letting my body loosen so they could whip me around like a rag doll until tight cuffs were placed around my wrists.

I’d never thought about how it might feel to be shoved into the back of a cop car in front of a crowd wondering who I was and what had happened. When a police officer places his hand on your head as he guides you into the back seat, you immediately realize you’re powerless. To begin with, the back seat of a police car is covered with hard plastic, so it’s extremely uncomfortable. The way your arms are sadistically handcuffed behind you makes your shoulders hurt. The metal handcuffs are angled just right to dig into your wrists, causing maximum discomfort and pain. And it’s hard to keep yourself upright since you can’t use your arms and hands to hold yourself steady.

I remember trying to reason with the police and let them know I was a Fordham University student-athlete. That my ID card was in my wallet. It was my only evidence beyond the gates of Fordham University to exclaim to society that I was a different type of Black person. Without one, I was just a Black kid on Fordham Road. With it, I was an educated student-athlete at a prestigious Division 1 college trying to obtain an education and avoid becoming yet another statistic. Same damn kid.

What is the price to pay for fitting such a description? I paid attorney fees in excess of $5,000, which my family and I couldn’t afford. I had to assemble character witnesses from all around Fordham University. Those who would be willing to testify in-person and through written affidavits attesting to my character. Eventually, I even persuaded a student eyewitness to testify on my behalf. She nervously accepted, knowing full well what could happen if I was found guilty of a felony charge. I would have to drop out of college, no longer run track, and walk through life with a criminal record that would serve as an albatross around my neck for the rest of my days on this planet. In a blink of an eye, everything in my life could change.

I could not imagine what transpired for other Black and Brown boys just like me who could not afford an attorney and lacked people of stature to vouch for their character. In most cases, they plead down their case and accept their unjust sentences. According to a study from the New York State Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the

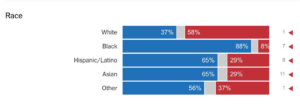

National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, 99% of all misdemeanors and 94% of all felony charges are resolved by a guilty plea. These are the souls who end up populating prisons in America. To add insult to injury, approximately 90% of all stops based on a suspicion of a crime in New York involve people of color.

Fortunately, I was a member of the 6% minority of felony cases. My case was dismissed. But before I could celebrate, the judge told me my arrest record wouldn’t be expunged until after 10 years of “good service.” That is, 10 years with no further crimes or infractions.

I was a 21-year-old senior in college—a soon-to-be college graduate with a waiting job offer at the largest health insurance company in New York. Yet, for the next 3,650 days, I would effectively be paralyzed as I navigated the streets of New York. My then goal: to avoid a New York City police force that was hell-bent on targeting young Black males. In fact, in 2005, the year of my graduation, there were 398,191 stop-and-frisk incidents in New York City. Of those, 352,348 (89%) of these individuals were found completely innocent; 196,570 (54%) of them were Black, even though we only represented 25% of the population in New York City that year. One of those incidents involved me. In fact, my Fordham hood was considered one of the top five neighborhoods in New York City where stops were done with a use of force 44.9% of the time.

Whenever you read or hear about a statistic, remember that behind those alienating numbers are red-blooded human beings with real lives, hopes, and dreams.

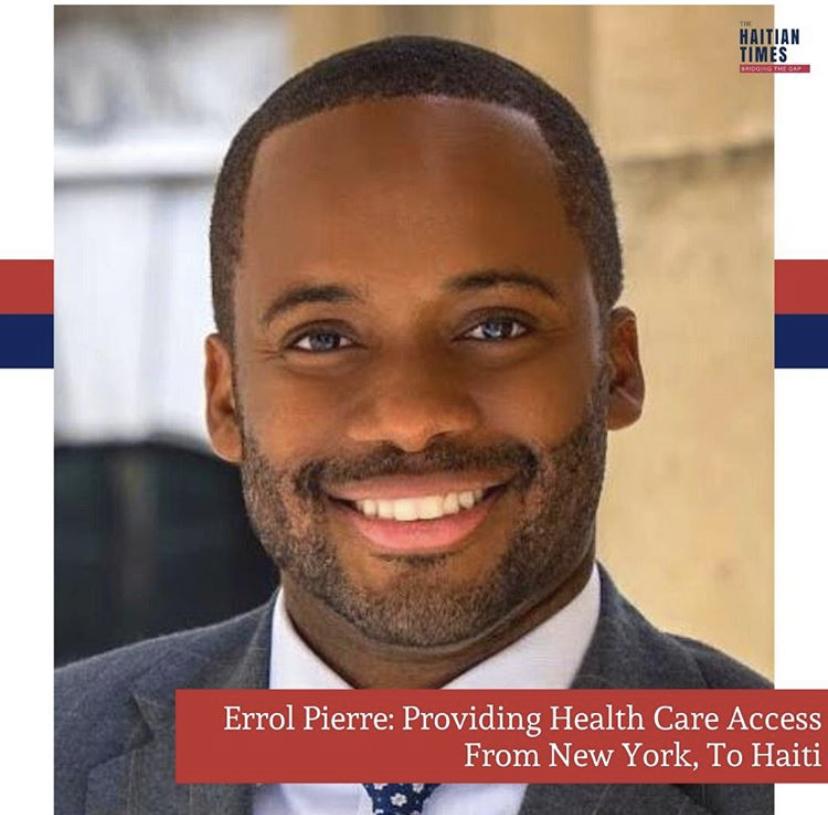

Errol Pierre is the author of The Way Up: Climbing the Corporate Mountain as a Professional of Color, and serves as a healthcare executive and college professor in New York. Opinions expressed are his own.